Agricultural Patriotism During World War I

Introduction

In commemoration of the 100th anniversary of U.S. participation in World War I, Special Collections continues its examination of the impact that the war had on NC State students, faculty, and campus. In this post, we explore how the university’s North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service (today’s NC Cooperative Extension) used its weekly publication Extension Farm-News to motivate the state’s farmers and farmwomen to participate in the war effort by appealing to their patriotism. (See also the 18 August 2017 posting of Special Collections News for more information on agriculture during the war.)

The Agricultural Extension Service implored North Carolina farmers to do their part to help with the war just days after U.S. entry into the conflict. The 14 April 1917 Extension Farm-News declared, “with the nation at war, it becomes the duty of everyone to produce food, to prevent loss, and to stop waste.” The May 5 issue stated, “This is a duty incumbent on all of us in order that we may feed ourselves most economically and at the same time help to feed those in the trenches.”

Patriotic Appeals to Boost Production

The Extension Service promoted grains and other commodities because of wartime shortages. Although North Carolina was not a major producer of wheat, the 21 July 1917 Extension Farm News listed the best wheat varieties to grow and recommended planting times, storage methods, and disease treatments. It also promoted production of other crops, corn most prominently, but also oats, barley, and others to meet war needs. It pushed for planting of beans as a “war-time suggestion” on May 26 and declared an “urgent demand for peanuts” on June 9. These appeals continued into 1918. On September 28 of that year, Extension complained, “light bales of cotton [were] hindering Uncle Sam,” and on October 26 it issued “an urgent appeal for nuts and seeds for gas masks” (filtration came from nut and seed charcoal). By November 2, when it expected the war to continue into the following year, Extension even promoted “patriotic big crop prizes for 1919.”

The Extension Service promoted grains and other commodities because of wartime shortages. Although North Carolina was not a major producer of wheat, the 21 July 1917 Extension Farm News listed the best wheat varieties to grow and recommended planting times, storage methods, and disease treatments. It also promoted production of other crops, corn most prominently, but also oats, barley, and others to meet war needs. It pushed for planting of beans as a “war-time suggestion” on May 26 and declared an “urgent demand for peanuts” on June 9. These appeals continued into 1918. On September 28 of that year, Extension complained, “light bales of cotton [were] hindering Uncle Sam,” and on October 26 it issued “an urgent appeal for nuts and seeds for gas masks” (filtration came from nut and seed charcoal). By November 2, when it expected the war to continue into the following year, Extension even promoted “patriotic big crop prizes for 1919.”

One way to boost agricultural production was through planting better seeds. As early as 9 June 1917 the Extension Service told farmers to save the best oats for next year’s seed, and it declared the first week of October as “Saving Seed Week.” A year later, it used its 26 October 1918 weekly to offer advice on “increasing production by saving and using good seed.”

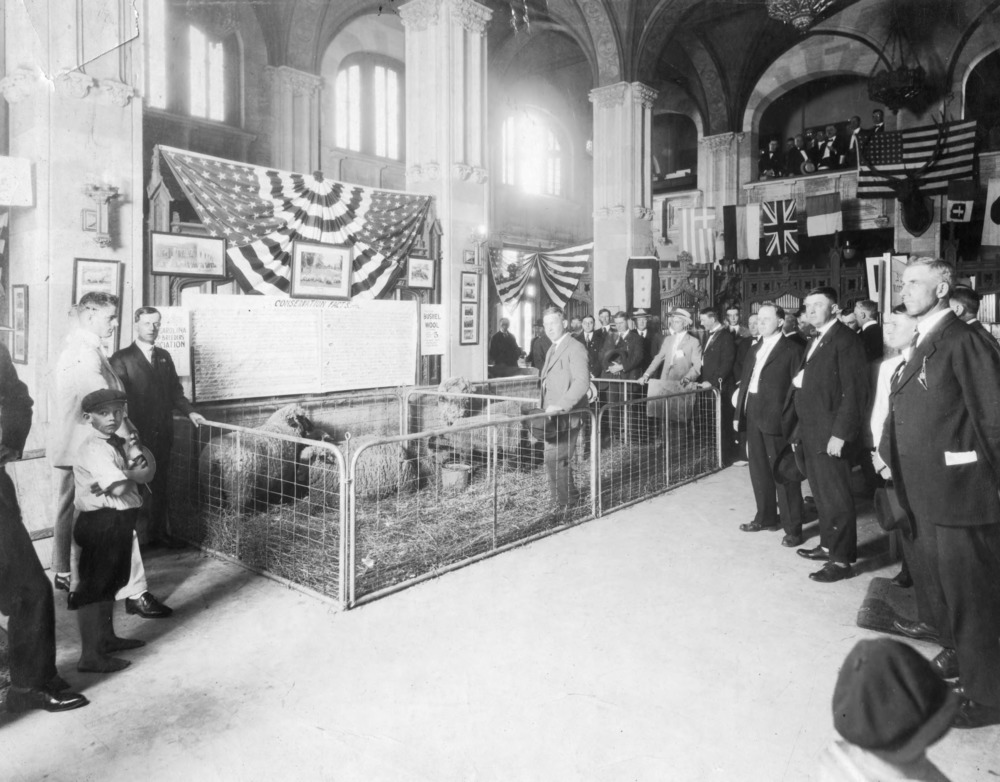

The Extension Service also promoted animal production, and one example was sheep. On 20 April 1918, it advertised “a series of patriotic sheep meetings and sheep-shearing demonstrations,” and on November 9 it stated, “. . . we have learned that sheep not only produce food and soil fertility, but also the clothing of the soldiers who are fighting this war for us.” Extension Farm-News also carried articles on “Culling of Fowls a War-Time Necessity” (24 August 1918) and “Effects of War on Animal Food Supply” (31 August 1918).

The Extension Service also promoted animal production, and one example was sheep. On 20 April 1918, it advertised “a series of patriotic sheep meetings and sheep-shearing demonstrations,” and on November 9 it stated, “. . . we have learned that sheep not only produce food and soil fertility, but also the clothing of the soldiers who are fighting this war for us.” Extension Farm-News also carried articles on “Culling of Fowls a War-Time Necessity” (24 August 1918) and “Effects of War on Animal Food Supply” (31 August 1918).

Insect Enemies and Allies

A growing awareness of the role of entomological science in agriculture let to special patriotic messages about insects. On 16 February 1918, the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service made “insect control a war-time necessity.” One pest interfering with wheat production was the Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor), ], thought to have originated in the enemy country of Germany. According the 8 September 1917 issue of Extension Farm-News, “it attacks early sown wheat especially, and it is said that the [German] Kaiser expects every Hessian Fly [sic] to do its duty by the [German] Fatherland this fall.” Similar thinking extended to pollinators. On 13 October 1917 Extension promoted the Italian honey-bee (Italy was a U.S. ally in World War I) as a replacement for the native variety: “Our wild honey-bees are known as “black bees’ and are native to Germany. The beekeeper who wishes to do the wise thing, which at the same time smacks of patriotism, will replace his black (German) bees with Italians, by introducing queen bees of pure Italian blood.”

A growing awareness of the role of entomological science in agriculture let to special patriotic messages about insects. On 16 February 1918, the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service made “insect control a war-time necessity.” One pest interfering with wheat production was the Hessian fly (Mayetiola destructor), ], thought to have originated in the enemy country of Germany. According the 8 September 1917 issue of Extension Farm-News, “it attacks early sown wheat especially, and it is said that the [German] Kaiser expects every Hessian Fly [sic] to do its duty by the [German] Fatherland this fall.” Similar thinking extended to pollinators. On 13 October 1917 Extension promoted the Italian honey-bee (Italy was a U.S. ally in World War I) as a replacement for the native variety: “Our wild honey-bees are known as “black bees’ and are native to Germany. The beekeeper who wishes to do the wise thing, which at the same time smacks of patriotism, will replace his black (German) bees with Italians, by introducing queen bees of pure Italian blood.”

Are You Doing Your Share to Preserve Food?

In addition to production, the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service also focused on the consumption side of the agricultural equation, and the Home Demonstration program played a prominent role. With the U.S. government promoting voluntary rationing of such food as wheat and meat, nearly every issue of Extension Farm-News contained food preparation tips during the war period. The 22 December 1917 issue featured “a war-time dish for meatless days” with cottage cheese as a key ingredient. The 5 January 1918 issue had “a practical weekly ration of flour, meat, fat, and sugar for the family.” An article titled “Is Not Cornbread Sufficient?” included recipes using barley and oat flour (11 May 1918); another stated that “cereals and legumes afford the cheapest food” (6 July 1918).

In addition to production, the North Carolina Agricultural Extension Service also focused on the consumption side of the agricultural equation, and the Home Demonstration program played a prominent role. With the U.S. government promoting voluntary rationing of such food as wheat and meat, nearly every issue of Extension Farm-News contained food preparation tips during the war period. The 22 December 1917 issue featured “a war-time dish for meatless days” with cottage cheese as a key ingredient. The 5 January 1918 issue had “a practical weekly ration of flour, meat, fat, and sugar for the family.” An article titled “Is Not Cornbread Sufficient?” included recipes using barley and oat flour (11 May 1918); another stated that “cereals and legumes afford the cheapest food” (6 July 1918).

Home Demonstration advocated canning to preserve food and eliminate food waste, yet wartime shortages created some challenges. Home Demonstration head Jane McKimmon promoted use of glass jars in the 5 May 1917 Extension Farm-News because “tin [for cans] is so scarce that it is our patriotic duty to save this for products which are to be marketed” (McKimmon also said in this article that “canning is agreeable work”). Shortages and high prices for sugar led to other substitutions: honey was promoted on 21 July 1917 and syrup on 10 August 1918. The 22 June 1918 issue was most blunt: “don’t waste sugar when canning.” Patriotic canning could be profitable, however, and create entrepreneurial opportunities; the 14 December weekly showed “how two canning club girls earned thrift stamp money."

Because of the sugar shortage, Home Demonstration tried to get the message out beyond North Carolina homes. On 21 September 1918 Jane McKimmon advocated that stores and restaurants use locally produced “muscadine grape juice for soda fountains,” replacing sugar-based soft drinks. A week later she promoted sorghum and other cane syrups in order to “keep the sugar going to the boys” in the armed forces.

Because of the sugar shortage, Home Demonstration tried to get the message out beyond North Carolina homes. On 21 September 1918 Jane McKimmon advocated that stores and restaurants use locally produced “muscadine grape juice for soda fountains,” replacing sugar-based soft drinks. A week later she promoted sorghum and other cane syrups in order to “keep the sugar going to the boys” in the armed forces.

During the war Home Demonstration repeatedly addressed other issues of food preservation and waste prevention. “Do Not Waste Skim Milk” commanded the 13 October 1917 issue of Extension Farm-News; it recommended using the liquid to make cottage cheese. “Save the Bread” was a message in 25 August issue. The 6 July 1918 issue of the weekly summed it up when it asked farmwomen, “Are You Doing Your Share?” to preserve food.

Other Special Collections News Articles about World War I

Robert Opie Lindsay, North Carolina's Only Flying Ace

From Somewhere in France: Letters from Alumni in World War I

Fred Barnett Wheeler: Alumnus, Soldier, Councilman, Mayor